Associating nature to Shinto deities, Japanese culture has always carried a deep respect and admiration toward the passing of seasons. This way, scholars and religious figures in Japan have long paid special attention to equinox days, associating all sorts of meanings to them.

As your personal guide to understand Japan and its traditions, 供TOMO is here today to tell you about one of those events: Shunbun-no-hi, the spring equinox.

A fairly recent festival:

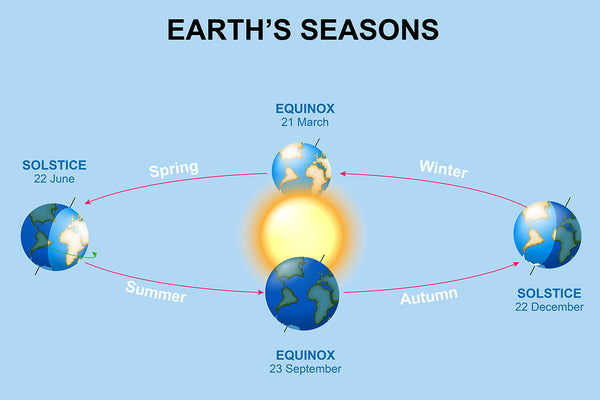

Celebrating the equinox or associating spiritual meanings behind solar events is a tradition found in countless cultures around the world. Accordingly, it is without a surprise that the Vernal equinox, where day and night time are equivalent, has always been regarded as of high importance. In east-Asia, the practice of honouring the dead can be traced back to ancient Chinese rituals, and was seemingly carried on throughout Japanese history. Peasants also often prayed for good harvests and thanked the gods for it.

In 1878, in line with a strengthening of the State Shinto, the Imperial Family called for celebrating the equinox as a way to honor the late emperors, a day named Shunki Koresai.

In 1948, as the State Shinto was definitely abolished and the religion freed from political influence, the occasion was relabeled Shunbun No Hi (Vernal Equinox), and lost on paper its religious significance.

What to do on Shunbun-No-Hi:

Shunbun-No-Hi is originally the central day in a full week of buddhist celebration (Haru-No-Higan), taking place three days before and three days after the equinox. There, followers were encouraged to practice introspection and reappraise their practice of Buddhism.

On the vernal equinox, the Sun is said to set on the furthest east point, therefore the Other World, Sukhavati (極楽浄土), situated on the east, is said to be confounded with this world, and communication with the deceased ones is made possible.

Nowadays, Shunbun-No-Hi is seen as an occasion to pay homage to the dead, notably by cleaning their tombs and making offerings, while sorting out things in one’s life and profoundly cleaning the homes. People therefore often take this day off to clean and wipe the slate clean both figuratively and practically.

How to do it:

When conducting offerings, Japanese traditionally leave food and flowers on their Buddhist Altar (仏壇). Interestingly, for the Vernal Equinox, the old custom is to place Botamochi, while people prefer Ohagi for the Autumnal Equinox. While the two sweets are technically the same thing, the only difference lie in the flower used to make them: Peony (牡丹) and Hagi (萩) respectively. Regardless, the sweet taste of the bean paste will be a perfect fit with the gentle bitterness of Cafe Genshin ! Be careful to start by cleaning the altar before making any offerings, as a mark of respect (since deities reject impurity). Then place water and offerings (have a look at our products for some ideas), often food that the deceased ones you wish to honour used to like. Finally, burn some incense, press both hands around your rosary and pray. However, do not let your food decay on the alta ! After some time, thank the gods for it and humbly enjoy the meal.

Moreover, the aforementioned ritual cleaning of tombs also follows a set of well-defined rules. Start by cleaning the graves and then burn incense. Then, pour water in a pail and use a ladle to water the graves. Finally, squat, sit on your haunches and pray, before doing a final bow as an ultimate form of respect and humility.